My sister lies in a recliner at the far end of the room, a still, poor mummy of a figure. The top of a cheap, flowered gown shows over the red plaid blanket in which she is wrapped. Near the ceiling above her, a TV blares unwatched.

My sister, the chatterbox. She loved people and loved talking, proud that she could start a conversation with anybody.

“This is New York,” I warned her when she visited. “Don’t talk to strangers.”

But she never met anyone she didn’t find fascinating and every day she came home sharing details about the “really interesting” woman she’d met on a bus, a man in the elevator, a grocery clerk.

Now she is oblivious to the other women who occupy the recliners on either side of her.

Her expression changes as I approach. Or, rather, various responses play across her face: recognition, surprise, then pleasure.

“It’s your sister,” I say.

I’m standing right in front of her, but I say “It’s your sister.”

“I love you, honey,” she says, immediately pulling my hand to her breast.

She knows me, then. I think she knows me.

She is unkempt. Her hair is no longer held back with combs but falls lankly around her face. Stubby gray hairs grow over her lip and on her chin. She is beyond caring, beyond even the smallest vanity.

“Is that a new gown?” I ask.

She glances down, fingers the edge of the dress, looking puzzled.

Once we ironed our clothes together every morning before we went to school. Remember, Lillian? You wore a little dickey collar under your sweater. A bright red scarf over your tightly curled hair.

I take her hand. Touch is everything now, maybe the only way to communicate. Her hand is small and pudgy and dry.

“Your little, chubby hands,” I say, holding them in mine, teasing her, wanting to connect, wanting her to know I love her. Her pale blue eyes, so near sighted, blink behind her glasses. She studies her hands bewilderedly.

Lillian, Lillian, I repeat, silently. Remember me, remember something.

“Those are nice glasses. They look good on you,” I say.

She struggles to tell us – her daughter and I — something about the glasses.\

“One is no good.”

“Oh, they’re nice,” I say, passing over what she is saying, trying to make it seem like a conversation.

Still, she struggles to convey something about the glasses. Then gives up.

“I’m nuts,” she says, finally.

“Join the club,” Carla, her daughter, my niece, says.

“It runs in the family,” I say, relieved to make a joke of it.

Finally, I take her glasses off her and try them on myself. They are clear, no correction at all, as far as I can tell. How can that be? She has always worn glasses and I know Carla has recently bought her new ones.

“These are clear,” I say to Carla. “There is no prescription.”

She shrugs. There are too many problems to deal with. This is not a big one.

All right, change the subject.

“Let me look at your legs,” I say.

I want to do something for her, to feel like I am caring for her in some way.

Like a child, she obediently pulls her gown all the way up so that part of her adult diaper is exposed. I slide the gown back down over her thighs.

“I’m going to put some lotion on your legs,” I tell her.

There is no place for me to sit, so I squat on the floor in front of her and slide a towel beneath her legs. She is completely passive. I rub the lotion on her legs – white like mine. Her feet are small and arched.

“Remember mother’s small feet?” I say. She seems to understand. “Yours are like that,” I tell her.

Surely, she remembers, surely she hasn’t completely forgotten the compact, powerful figure of our mother? A mother she loved more than I did.

Was it just two or three months ago I was squatting before her, just as I am now? She was still at home, still able to hear me, to tell me things. She had asked me to help her put her shoes on.

“Somebody gave me some socks,” she said, “but I don’t wear socks anymore. They’re too uncomfortable because of my toes.”

Her poor, misshapen feet – she had always had hammer toes.

I pretended to study the socks a moment, then said,

“The socks are fine, but the toes have to go.”

She burst out laughing, the kind of full throated, delighted laugh that always made me laugh, too. And we laughed together, like we used to do.

Now, the skin is dry and rough on her feet and I press the lotion in with a circular motion. Hoping she is feeling its coolness, hoping she is feeling my hands on her, hoping she is feeling loved and cared for.

She frowns as she struggles to put together a thought, to let me know what is going on inside. Her face is deeply lined, her small eyes worried and anxious. I feel myself straining towards her, wanting her to tell me something. Wanting to understand.

There was a “bad night,” she says, her eyes begging me to understand. “Things came out.”

She looks at her hands and arms. Is this the same delusion she had weeks ago – when she kept repeating about the “things” that were inside her and came out? Her words call up horrible images from a sci-fi movie — monstrous, slimy aliens bursting out of the bodies of their human hosts.

“Your sister cries and screams,” the caretaker has told me, sounding annoyed and disapproving.

My sister, who never cried, who was afraid of sadness, because sadness was too terrible, too deep and overwhelming. But now she cries.

She is trying to tell me something again. It sounds like it might be about our childhood, in Alaska, in the roadhouse.

“Two little girls,” she says.

Us? Is she talking about us? There was always us, Lillian, always the two of us, when there was no one else.

Once she says “mother,” then quickly “grandmother.” But nothing more.

God, just give her peace of mind, I pray. That’s all I want for her now.

“Don’t worry,” I say.

“No worries,” Carla says.

It is lunch time and I encourage Lillian to go to the table. She is unsure.

“Is it all right?” she asks.

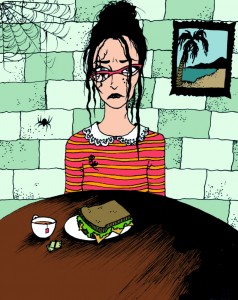

But once she is seated at the table with the others — three women in varying stages of madness — she seems to have forgotten about us.

Maybe this would be a good time to go, when she is preoccupied and will not notice. But I can’t go yet. Not yet. Instead, I pull up a chair by her side and watch while she eats, dumbly, unconsciously, half a liverwurst and cheese sandwich.

Remember, Lillian, during the war years there in San Francisco, meat was rationed and the only meat we could get without a coupon was liverwurst? And how sick and tired we were of eating it?

“Is that good?” I ask.

Remember the quiet old flat there in the Mission District, how you dressed up every day and took a street car up Market to work in a big office building? You wore stylish little hats and silk blouses with sequins, fine wool suits and high heeled pumps. You carried a clutch bag tucked under your arm and sat at a shiny desk, so proud of your skills, of your well-groomed appearance.

“Was that good?” I ask again.

“I could have another one,” she says.

Well, that is clear enough. It was only a small half a sandwich. Does she get enough to eat? Do they pay attention, see that she wants more?

I ask the helper for another sandwich for my sister.

“Oh, I forgot, she always eats a whole one,” the helper says.

They forget. That is the way it is when you are a sick, mad, incontinent old person. Who will remember?

“Don’t go,” my sister says, pulling my hand across her breast as I stand to leave. Her eyes are pleading, her mouth beginning to tremble. “Will you be back?”

“Soon,“ I say.

“When ?” she asks. This evening, tomorrow?

But she has no concept of time. It wouldn’t matter what I say.

“Don’t go,” she says, “don’t leave me.” She starts to cry. I put my arms around her and she is crying on my shoulder.

“I’ll be back,” I say. “I’ll call you. I’ll come again.”

Thin, weak, hopeless lies. I don’t know when I will see her again.

I pray that she will forget, forget me the instant I leave.

And now, the long journey home. I sit on the train staring out the stained and dusty window. Stunned more than sad, not ready, not able, to think about what has transpired.

Beyond the window, a vast, sunlit pasture. Dark, heavy forms — placid, statuesque black angus cattle – are outlined against the golden land, against the late California sky.

The train moves on, the pasture disappears. Now a chain of small mountains rises into view, silhouetted against a huge sky. The horizon etched with pink, the open sky stroked with smoky gray clouds whirling upward toward the heavens.

So much beauty. It is impervious to sadness, to pain and hopelessness. Eternal, enduring. For these moments, for these fleeting moments, I accept the healing grace of beauty.