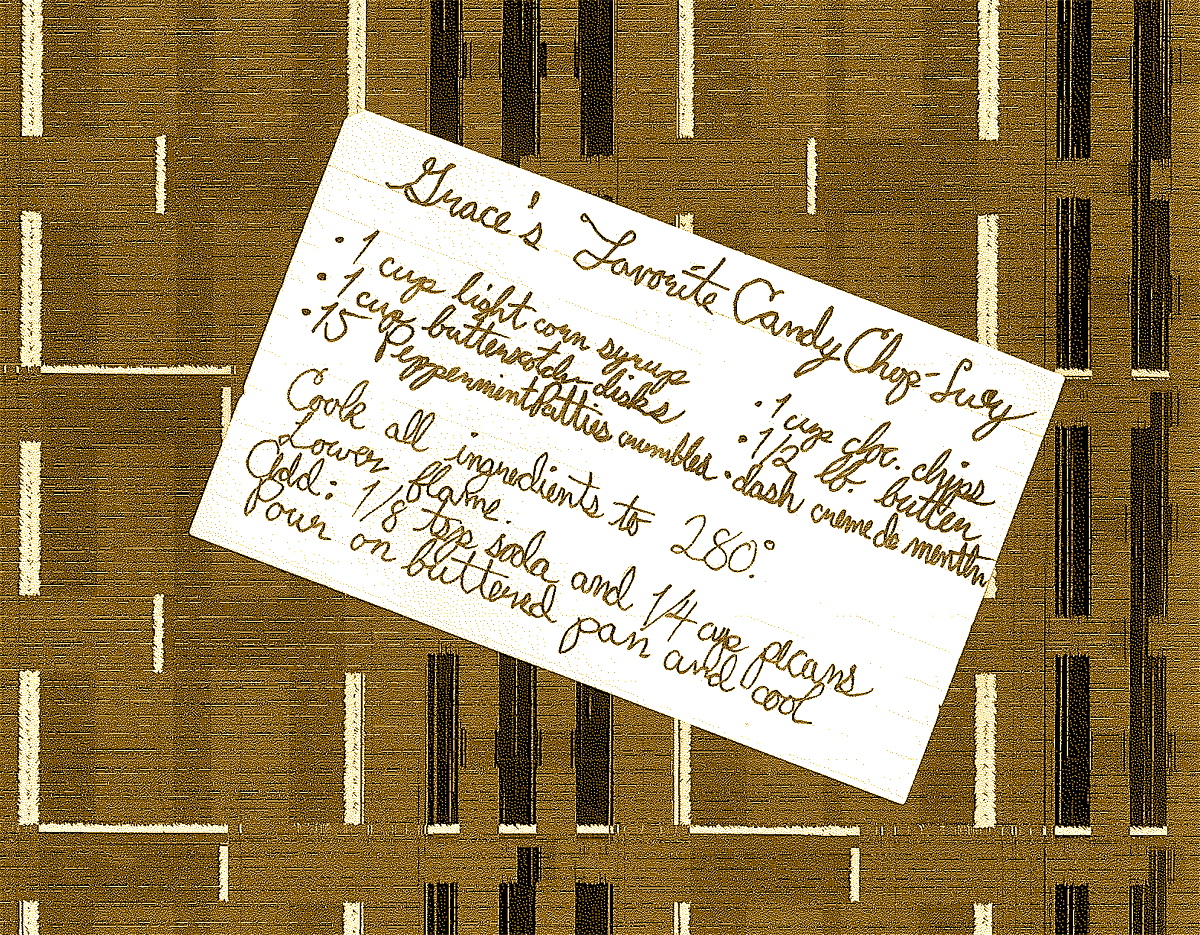

Rummaging through a stained and greasy tomato box that mainly contained pieces of things that offered no clues about the things themselves, Sandy came across a small tin. The lid squeaked as she opened it. Inside were scores of yellowed index cards, each covered in fluid script. They were recipes, written by a woman who had no doubt learned how to write when handwriting betrayed one’s education. Each card conjured images of an idyllic family and their dinner rituals. The planning, the care, the time spent, the smells, the heat of the oven, cinnamon—always cinnamon.

Flipping through the cards she tried to imagine the woman who had prepared meals called “Knuckles and Mash,” “Chicken Fried Parts,” “Peanut Butter Soufflé,” and, simply, “Knitted Hearts.” Maybe, she thought, the recipes were a more accurate description of their owner’s upbringing than the handwriting.

She decided to buy the tin full of promised meals. Sandy knew she would never take the time to make “Oil Salad” or “Clothesline-Dried String Beans,” but to her the tin was a relic from a romanticized time, like a bullet found on a Civil War battlefield, or a black and white movie where everyone spoke too quickly and both the kisses and the gunshot wounds were dry. It was a biography of a life she would never live, a life filled with fears and hopes and misfortunes not unlike her own and yet so radically different that it was more a curiosity than an actual life. She wondered if some day someone would be sifting through the litter of her existence thinking these very thoughts. Doubtful. Who would be nostalgic for her time?

She decided to buy the tin full of promised meals. Sandy knew she would never take the time to make “Oil Salad” or “Clothesline-Dried String Beans,” but to her the tin was a relic from a romanticized time, like a bullet found on a Civil War battlefield, or a black and white movie where everyone spoke too quickly and both the kisses and the gunshot wounds were dry. It was a biography of a life she would never live, a life filled with fears and hopes and misfortunes not unlike her own and yet so radically different that it was more a curiosity than an actual life. She wondered if some day someone would be sifting through the litter of her existence thinking these very thoughts. Doubtful. Who would be nostalgic for her time?

She placed the tin on the card table set up by the front door. The woman guarding the gray cash box looked old enough to be dead herself, but once she saw what Sandy had put before her she came to dusty life. “John!” she bellowed in a voice that belonged to someone younger. “It’s Mother’s tin!”

An even older man, held together by nothing more than a tight belt and a determination not to fall apart, shuffled to the table. John picked up the tin with flabby fingers—so loose was his skin—opened it, and picked a card at random.

“‘Unboiled Soup.’ Remember that one, Grace?” he said.

“Everything Mother made had a name,” Grace said to Sandy. “I think she tried to make the world better by giving everything a name, like you might do to a stray puppy that eats tissues.” Grace turned to John. “Do you remember Carl, that stray puppy who kept eating all our tissues?”

“Sure do. Had to clean up after the thing all the time. Stupid Carl.”

“He just needed fiber.” Grace looked at Sandy. “I’m sorry. I can’t take your money.”

“I understand,” Sandy said, trying not to sound disappointed. “It has great sentimental value. I don’t need it after all.”

“Oh no no no,” Grace said. “You misunderstand. I want to give it you. It’s much too valuable to sell. Just take it.”

Sandy, unaccustomed to kindnesses, no matter how small, held the tin like a thin-shelled egg and said nothing.

“There is something I must ask, though,” Grace said.

“What’s that?” Sandy asked.

“You have to make a dish from that box every year, on June sixth. That’s Mother’s birthday. Every year. Don’t forget.”

Tears filled Sandy’s eyes. “I won’t,” she said. “I promise I won’t.” She stumbled out the door, crying.

John watched Sandy until she drove away. “Now what did you do that for, Grace?” he asked. “Even stupid Carl would spit out Mother’s food.”

“Just trying to get rid of everything Mother left us, and that included the misery,” she said. “Now if only someone would buy that damned Victrola.”